251

Followers

4

Following

Manny Rayner's book reviews

I love reviewing books - have been doing it at Goodreads, but considering moving here.

Currently reading

The Greatest Show On Earth: The Evidence For Evolution

R in Action

Fluid Concepts and Creative Analogies

McGee on Food and Cooking: An Encyclopedia of Kitchen Science, History and Culture

Epistemic Dimensions of Personhood

Pattern Recognition and Machine Learning (Information Science and Statistics)

Relativity, Thermodynamics and Cosmology

The Cambridge Handbook of Second Language Acquisition

Many of my all-time favourite books make the list because they show you what it's like to be inside the mind of an extraordinary person. While you're reading them, Churchill's History of the Second World War and Yourcenar's Mémoires d'Hadrien let you be a great statesman at a pivotal moment in history. Simone de Beauvoir's autobiography, more than any other book I know, gives you the feeling of being a major literary figure. Polugayevsky's Grandmaster Preparation, which many chessplayers treat almost as a sacred text, is the only truly honest account I've seen of how a top Grandmaster thinks.

Many of my all-time favourite books make the list because they show you what it's like to be inside the mind of an extraordinary person. While you're reading them, Churchill's History of the Second World War and Yourcenar's Mémoires d'Hadrien let you be a great statesman at a pivotal moment in history. Simone de Beauvoir's autobiography, more than any other book I know, gives you the feeling of being a major literary figure. Polugayevsky's Grandmaster Preparation, which many chessplayers treat almost as a sacred text, is the only truly honest account I've seen of how a top Grandmaster thinks. Penrose belongs in this select company: I finally believe I have some idea, no matter how faint, of how a great mathematical physicist sees the universe. Like the other books, it's not an easy read. You can't build up this kind of picture without including a huge number of details; if you took them away, the whole texture of the world would disappear with them. Churchill needs the maps, troop movements and political networking. De Beauvoir has to assume (in my case, alas, incorrectly), that you're conversant with most of French literature. And if you removed the chess from Polugayevsky, there wouldn't be any story.

In Penrose's case, it's mathematics and physics: he resolutely refuses to dumb it down, and includes a seriously frightening quantity of Greek letters. If it really were true that every equation halved your sales, he would not have sold a single copy. What saves him, and makes the book readable to non-experts like me who at least have some mathematical background, is his uniquely visual way of experiencing mathematics. Penrose can obviously hack the equations, but he also has to see them, and he is astonishingly resourceful at coming up with visualisations. The ones I liked most had to do with Special Relativity. You may recall this fairly well-known picture by Escher:

What I didn't know was that it illustrates the "hyperbolic geometry" which underlies Einstein's Special Theory. In Special Relativity, the speed of light is an absolute limit, so velocities can't simply be added: the correct formula for combining them is the one shown in the picture. You can add any number of fish together and never reach the edge; similarly, no matter how many time you add a velocity to itself, you never get to the speed of light. Believe it or not, the diagram exactly models the equation! And another geometrical argument he used here is nearly as beautiful. A great deal of nonsense has been written about the "Twins Paradox" (for example, by Robert Heinlein). Penrose's explanation is wonderfully concise and elegant. In Minkowski-space, a straight line is counterintuitively the longest distance between two points. The twin who flies out into space has a less straight world-line than his twin who stays at home, so he ages less. Thanks to Penrose, I can now see it.

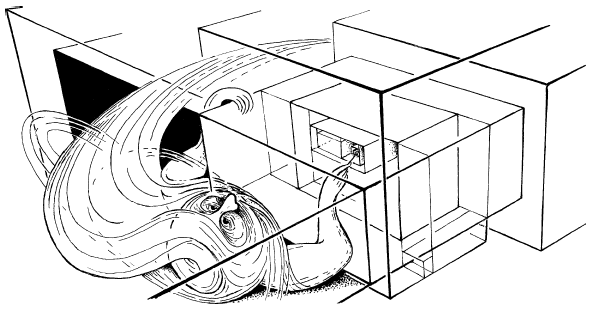

It turns out that theoretical physics is anything but a dry technical discipline: you come away feeling that these people are visionary poets who have chosen to write in mathematics rather than ordinary language. Blake is one comparison who came to mind, and I can't resist the temptation to juxtapose Blake's image of God:

with Penrose's:

If you're wondering what God is doing, it's actually pretty much the same as in Blake's version: the picture dramatizes the extremely low entropy of the Universe immediately after the Big Bang. I had not previously appreciated how remarkable this is, and the puzzle it represents is central to Penrose's exposition. Once again, the picture isn't gratuitous. He's illustrating, in a humorous way (the book is often funny), an extremely serious point.

As I've said, it's not an easy read. It demands a great deal of concentration, and I think I must have spent at least two or three hours a day over the last month ploughing my way through it. A lot of that time, I was supposed to be doing other things, but I'm glad I ignored them and read Penrose instead. He's changed my way of looking at the world as much as Dante did when I read The Divine Comedy in 1999.

Now, if only it were in terza rima with animated illustrations by Gustave Doré and Terry Gilliam. Then it would truly be perfect.

_____________________________________

We had another CERN physicist to dinner last night, an Australian post-doc who's working on validation of the Standard Model. I asked her if she'd read Road to Reality.

"I stopped reading popular science books when I was an undergraduate," she said apologetically.

I said it wasn't really a popular science book, and she opened it for a few seconds. "Hm, yes, it does seem to have quite a lot of equations," she muttered doubtfully, and then she put it down again.

Something seems to have gone slightly wrong with the marketing campaign for this book: laymen think it's a book for physicists, and physicists think it's a book for laymen. I'm reassured to see a fair sprinkling of reviews here from people who give every appearance of having read and enjoyed it.

1

1